Sinnlichkeit

Designing for senses, designing for inclusivity

It’s a Wednesday evening and I am having my routine walk. My hands in my pockets navigating the crowd and keeping my ears open.

Finally, I get to an area I can sit down and take everything in. Its ambience filled with birds flying, faint sounds of people talking, playing music, cars and it’s the golden hour—the sky looks so beautiful. The gentle zephyr and petrichor has me reminiscent of my childhood days in Sapele, Delta State.

Many things are happening at once yet I am able to perceive and make sense of everything. My sense of vision, audition, olfaction and touch all working in tandem gifting this euphoric experience. But a few days earlier, I’d watched something that made me question how many people could enjoy this same experience.

1.3 billion Stories

I was watching a YouTube short a few days prior to my walk and it was interview with a blind man and he was asked if the concept of distance made sense to him. He said, it didn’t. This was both shocking and concerning to me as I had never pondered about it, what it’s like to live without sight. I wanted to know—what do they see? I searched and an individual who’s completely blind doesn’t see darkness or blankness. They see nothing, just like how you and I can’t see the back of your head. Without a mirror or camera of course.

An estimate of around 1.3 billion people live with disabilities today that’s 1 in 6 (World Health Organisation, 2023) and in Nigeria, my country it’s 35.1 million (National Commission for Persons With Disabilities, 2023) that’s 17% of our population.

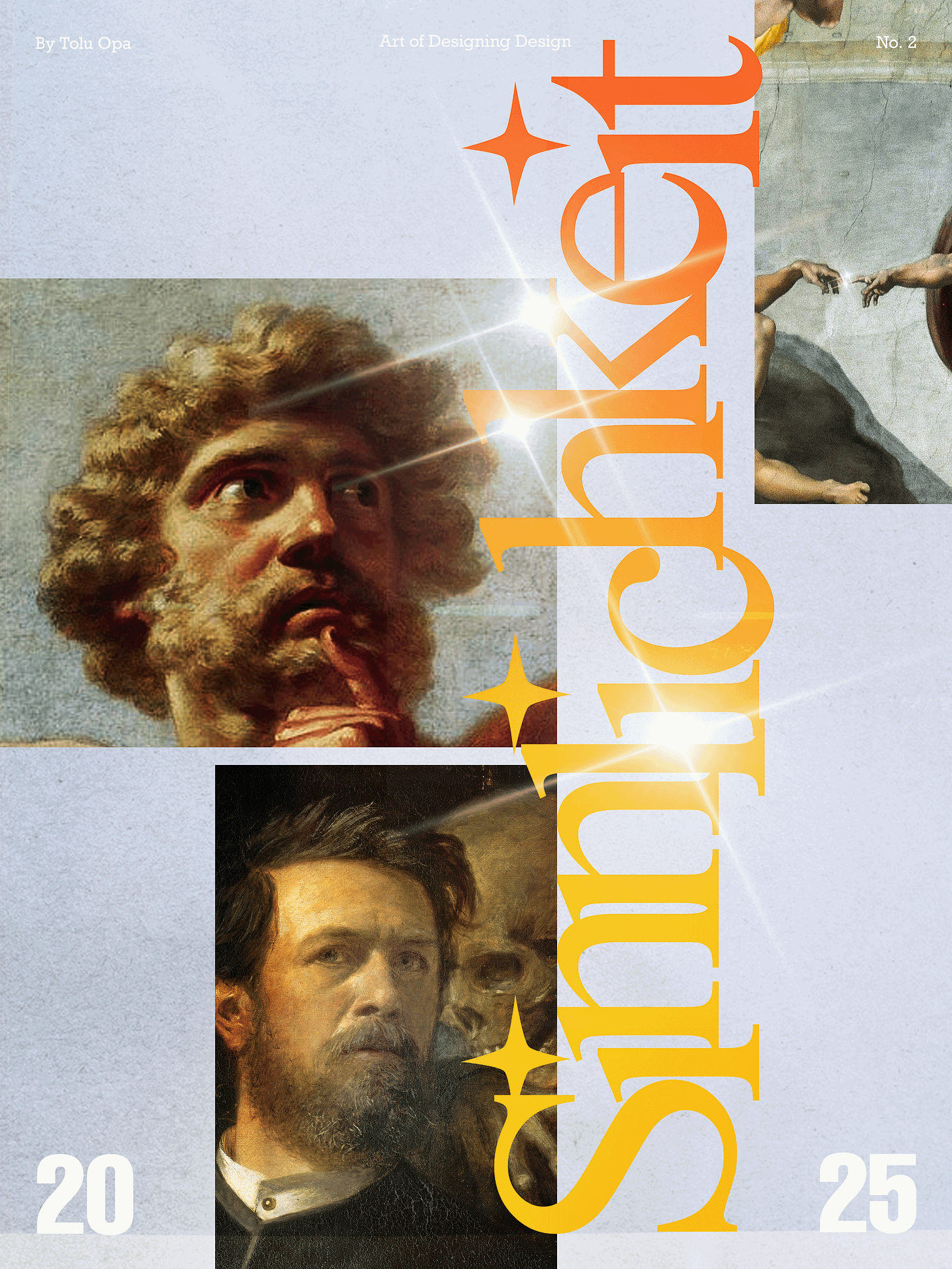

Now not everyone who has a disability with their vision is blind, of course. They can still see but if we got each of them into the room and asked them to look at a picture let’s say Heinrich Fueger’s Prometheus Brings Fire to Man—all of them would see different versions of the picture and a blind person sees nothing at all. To be able to give them a feel of what its like we have to tell them what they are supposed to see. Whilst walking some have to use glasses, sticks, dogs or have a chaperone who guides them making sure they don’t run into someone or something.

There are people with hearing impairments who can’t hear at all or hear the world we live in clearly and there are people who have certain difficulties with feeling or holding or using objects.

Design That Benefits Everyone (The Curb Cut Effect)

In my junior year, I learned about the Curb Cut effect—a phenomenon where features designed for a specific marginalised group end up benefiting everyone. The name comes from those small ramps at street corners.

I understood this to some extent because in my hostel in university there were curb cuts but that was about it. There were hotels with automatic doors but it wasn’t a standard in restaurants even local government buildings.

There is the belief that disabled individuals are cursed and hopeless. Some of them are sent out to beg for alms for economic reasons. Nigeria as a society hasn’t been built for inclusivity and this is disheartening.

In other places in the world, we have seen products and laws designed to be inclusive.

In the United States, there is an Americans with Disability Act that requires an elevator door to stay open long enough for individuals with disability issues to board safely and only after the allotted time will it close.

Elevator buttons with braille markings, traffic lights with standard colour codes, low floor buses, the sound of a truck reversing and audio signals at pedestrian crossing are some of the few design choices made for disability in public spaces which now benefits us all.

Digital spaces have evolved too. Alternative text describes images for screen readers. Keyboard navigation serves those who can’t use a mouse. Captions provide text versions of audio for deaf or hard-of-hearing users. High contrast modes help people with low vision or color blindness. Each feature designed for specific needs but often discovered and appreciated by everyone—like reading captions in a noisy coffee shop or navigating with a keyboard when your mouse battery dies.

Over the years there are many products that have been designed and many meet requirements in terms of accessibility. We can always make previsions on how our users are going to use our products but in the end our products may end up being used in ways we never imagined and fulfilling a greater cause.

Meta Ray-ban display

Late one night, I saw some tweets on X (Twitter—and for me it’ll always be Twitter) Meta being live. I stopped my scrolling and joined immediately.

Bereft of sleep, I was initially wowed by the fact we have been able to cram this level of technology into a form factor so small yet functional and attractive. Then there’s the live demo and this is what strikes me the most, live caption. The ability to see a live caption of whoever I am talking to, a translation of what they are saying into my native language. As Mark Zuckerberg said, “this is a game changer” yes, for everyone and for anyone who’s hard of hearing or deaf and it benefits everyone. Imagine being able to move from UK to Spain without needing to pull out your phone to translate every sign post from Spanish to English. Or two Meta Ray-ban display users who speak different languages facing each other and having a conversation in their native languages maybe one in Russian and the other in Arabic or Mandarin.

Apple

Apple has consistently built products that help people fully participate in life’s adventures, both small and large.

August last year, they made a short cinematic film featuring real disabled individuals. The film shows how the products they have engineered empowers these individuals from their daily activities to levelling the playing field between them and their competitors whilst also fostering shared humanity.

Going back to August this year, it seems they have a knack for wanting to harvest everyone’s tears every August. August this year there was a cinematic video, of a man, Brett Harvey. He has been living with Parkinson’s for the past 6 years. In this video he uses action mode in recording his son whilst he rides his bicycle.

Action mode is a feature which helps stabilise the videos we take and looking at the video you can’t say, “Oh! the video recording was shaky. Urgh, it’s not good enough the—memory is ruined.” No, it’s that good—it captures, processes and gives us that video experience we are looking for. He uses voice commands to take the video.

Imagine what this does for individuals who have lost their fingers or an arm? It means through these thoughtful considerations we have been able to engineer a product which meets the need of a plethora of people—equipping them with tools that’ll allow them experience the beauty of the world like nothing happened.

The Responsibility We Share

Whether you’re a product designer or not, we’re all engineering solutions in some capacity. And in those moments of creation, we have a choice: design for everyone, or design for some. The small considerations, voice command, caption, the curb cut—might seem minor, but they’re the difference between a good product and one that changes lives.

I ask myself when designing, is this a gimmick, or will this genuinely improve someone’s experience? Because when we design with intention and empathy, we build a world where everyone gets to experience their own version of that golden hour walk, in whatever way makes sense to them.

this is really good my guy!